Japanese/Chinese Words Series Pt. 1: 8 Words with the Same Character, but Different Meanings

Japanese is one of the most difficult languages in the world to learn, due to it employing three different character-systems: hiragana, katakana, and kanji. The kanji characters originated from Chinese characters, and while most of the meanings remain intact, a few specific words have somehow adapted completely different meanings. Here we will examine 8 of the best examples to demonstrate how the same characters can be understood in two very different ways when they are read as Japanese or Chinese.

- 面白い omoshiroi

In Japanese, 面白い means funny or interesting. You may encounter this very commonly-spoken word on advertisements too. In Chinese, however, this means “white face” or “pale face” but not in the racial term, but as in “you look like you’re about to faint”. That certainly is no laughing matter.

- 勉強 benkyou

Everyone who has studied Japanese should know this word. 勉強 is the kanji for “study”, as in 「私は日本語を勉強します」for “I study Japanese.” This word baffled me the first time I encountered it in Japanese, because in Chinese, to 勉強 is “to endure grudgingly”. Many people can certainly draw the connection and relate to personal experiences.

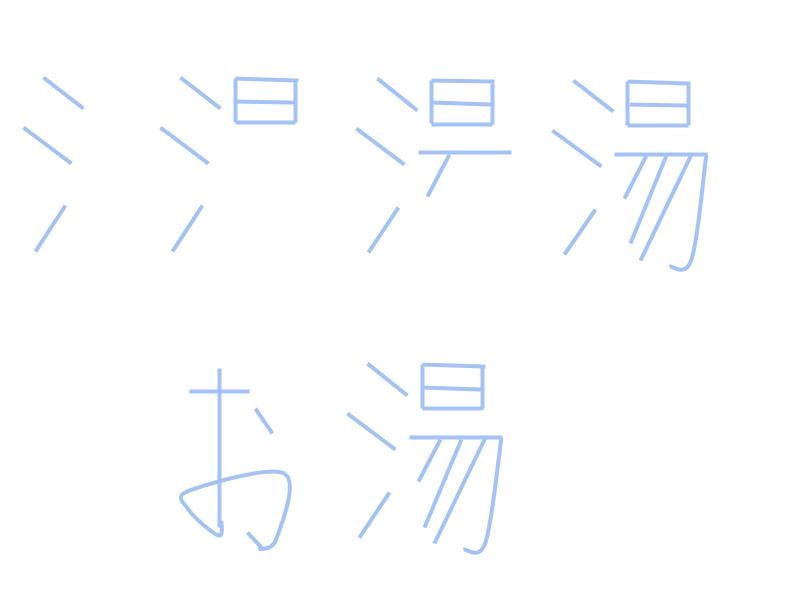

- お湯 oyu

At a restaurant or a hotel, this word is certainly visible here and there at the water dispenser or the sink. お湯 means hot water in Japanese, but in Chinese, it adds more. 湯is “soup” or “stew” in Chinese. Imagine when you’re getting ready for a bath and the label on the water tap indicates soup. It must be disappointing that you in fact cannot fill the bathtub up with clam chowder.

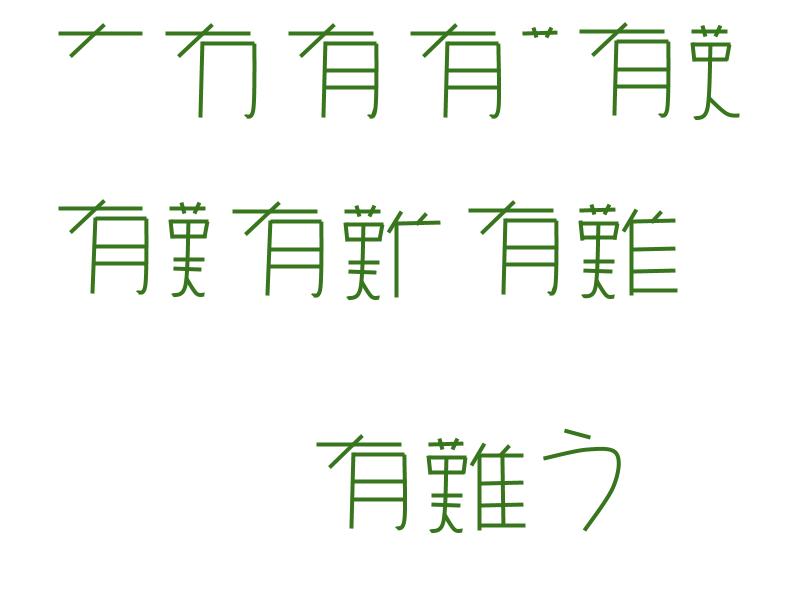

- 有難うarigatou

It’s rare to see this written out in kanji characters, but this can definitely confuse the heck out of Chinese visitors. 有難う, the word of saying “thank you” has the completely different meaning of “having trouble”. To see a postcard that shows appreciation towards another, one may misinterpret it as a call for help!

- 大丈夫 daijoubu

When you see someone get hurt or looking ill, you can ask a quick “大丈夫?” to ask “are you okay?”. The other person may reply with “大丈夫です” meaning “I’m okay”. In Chinese, this phrase means “a real man” in the stereotypical perspective. Take out the 大 or “big” and you get 丈夫,or “husband”. So to see “are you okay?” written out, it may be mistaken by a Chinese speaker as asking “are you a real man?”

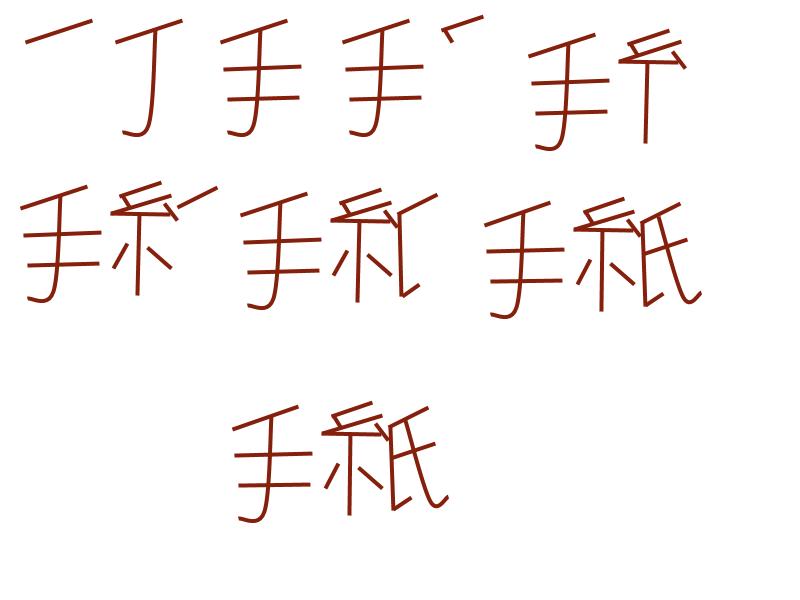

- 手紙 tegami

During your time in Japan, you may want to send a physical手紙,or “letter” to your friends or family using the beautiful Japanese letter papers. Slap a Japanese stamp, slide it into the mailbox, and it’s an excellent souvenir to send mid-trip. In Chinese, however, it means “toilet paper”…… Oops.

- 切手 kitte

To send your toilet pap…… I mean, letter, you need to get a stamp. You can easily purchase a 切手 from one of the numerous post offices or convenient stores in the country. In Chinese, however, the words mean “to cut a hand”. I am very certain that wouldn’t get delivered anywhere.

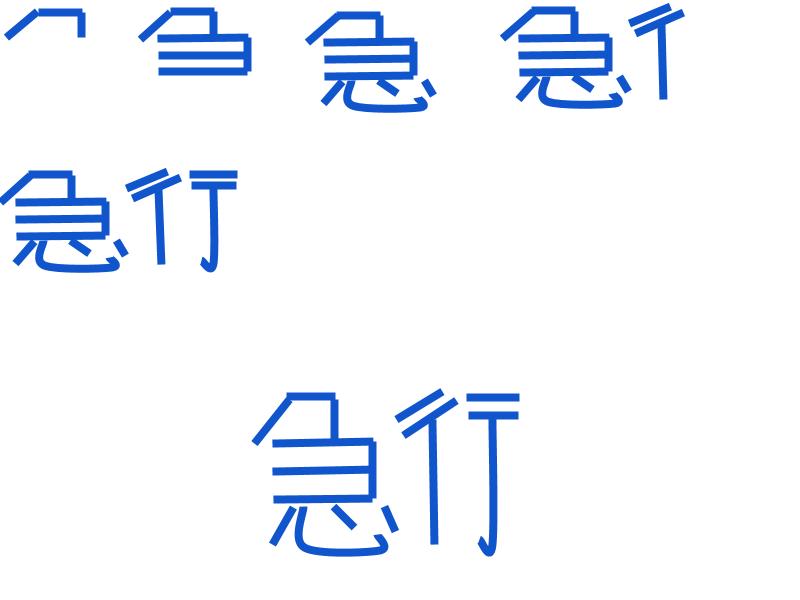

- 急行 kyuukou

急行 is a common word to see when taking public transportations in Japan. Trains with this kanji indicate that they are rapid trains that will skip certain stations and reach your destination faster. When matched with its Chinese meaning of “walking fast”, I suppose the logic-train of this one isn’t as off-track as the others.

Students of both Chinese and Japanese languages have probably encountered many of the examples above and were likely puzzled by how such hilarious gaps of meanings came to be. We will cover some more in the future, so stay tuned and share the knowledge!